Restorative Pruning

It Takes More Than a Nip and a Tuck, but You Can Bring Those Old Trees Back Into Production

By Guy K. Ames, NCAT Horticulture Specialist

Long-neglected fruit trees quite often simply die of disease or trunk borer damage, especially in the South where I live. But if they don’t die, one of the two most common problems with aging fruit trees is growth so tall that the thought of pruning and harvesting them just seems impractical and intimidating. The second most common problem is that old, overgrown trees tend to become unproductive, especially of good quality fruit. “Restorative pruning” or “rejuvenative pruning” are terms used to describe techniques to bring old, too tall, and unproductive trees back to a manageable and productive state.

A Central Principle

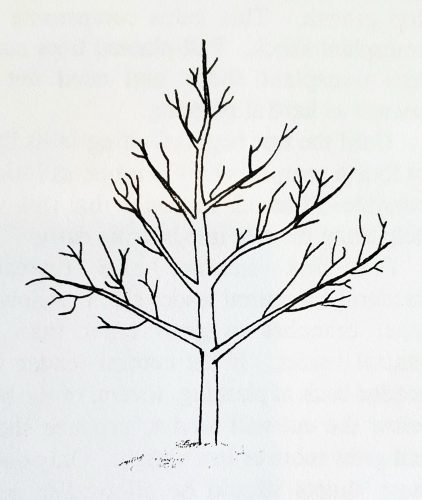

Ideal central leader form. Illustration courtesy Guy Ames.

Starting with the tree that is simply too tall to efficiently manage, we must first determine what the natural growth habit of that tree is. Apples, pears, and—to a slightly lesser degree—sweet cherries naturally assume a more-or-less pyramidal form, with one so-called “central leader” taller and stouter than any other upright growing shoot. Such trees are described by horticulturists as exhibiting “apical dominance,” meaning the apex or top of the tree dominates the growth pattern of the overall tree. When this natural growth habit is violated—that is, when the central leader is cut back to any significant degree—the tree will likely respond by sending up many, many candidates to be the new leader. It’s like a king or queen that dies without heirs. Many pretenders to the throne will arise!

And the further down the trunk you cut the central leader, the more these vertical shoots proliferate and the more vigorous these shoots will be. They will crowd the center of the tree, blocking sunlight and air. Such vertical shoots tend not to be fruitful. So, then, the first principle to respect in bringing down the height of a central leader-type tree (apples, pears, and sweet cherries) is to not try to cut out too much at once. Don’t try to cut a 30-foot tall apple tree down to 12 feet in one fell swoop! Plan for a two, three, or four year process, depending on the size of the tree currently.

The Modified Central Leader System

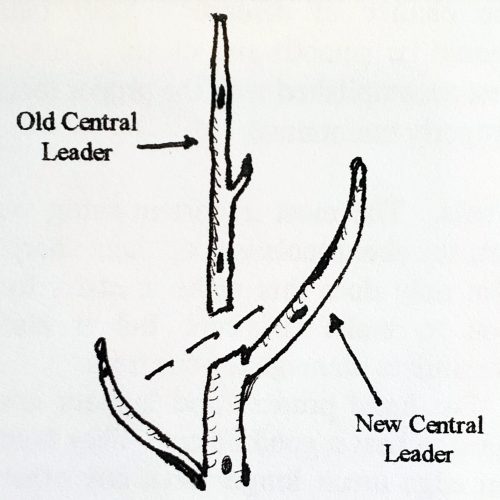

Modified central leader cut. Illustration courtesy Guy Ames.

At the same time and just as important, when you’re cutting back the central leader, pick another more-or-less upright growing shoot to become the new central leader. This new central leader will probably arise from the same main trunk. It should be a few feet shorter than the leader you cut out. Once you’ve chosen the new central leader, other serious contenders for tallest shoot should be cut back, preferably to a more horizontal growing limb. This pruning/training system is called “the modified central leader” system. That, or the “multiple central leader” system (see below), should be the way you maintain the desired height of a fruit tree once it first reaches the desired height. In other words, you will probably be choosing a new leader each year after the tree reaches the height you want.

The Multiple Leader System

When you’re faced with a very large, old tree, a new central leader may not be enough. In such cases, choosing multiple leaders might be the best choice. In essence what this will look like is three or four “secondary trees,” all growing and contained in the canopy space of the original, single tree. Instead of having one big pyramidal tree on one big trunk, you’ll have two, three, or more secondary trunks branching off of the main trunk.

Each of these secondary trunks, then, will have its own central leader, resulting in multiple leaders for the tree as a whole. To be honest, it’s probably rare that such a tree ever looks perfectly balanced among the several secondary trees. That is not important. What’s important is that you maintain the trees “need” for apical dominance among these several secondary trunks. If you don’t choose a leader or leaders yourself, the tree will waste energy and crowd the interior of the tree with multiple wannabe leaders.

Big Thinning Cuts

The sheer amount of wood in an old tree can be intimidating! For this reason alone, after choosing the new leader(s), you will serve your purposes best if you focus on removing a few big branches. An important—maybe the most important—purpose of pruning is to thin out the interior of the canopy for sunlight and wind penetration. An old rule of thumb is that a full-grown robin should be able to fly through the tree’s canopy. Removing any large branches that are growing straight up (not including the central leader!) or back into the center of the tree is a good place to start. And making thinning cuts rather than heading cuts will make your work lighter next year and the year after that.

To fully understand the distinction, especially the tree’s response to these different types of cuts, refer to ATTRA’s Pruning for Organic Management of Fruit Tree Diseases. But basically a thinning cut is cutting a branch or shoot back to where it joins with another branch or the trunk. In other words, where a branch forks, take off one fork, usually the one growing the most upright or back into the interior of the tree. To repeat, restorative pruning relies on opening up that tree, so stand back and look at the tree. See if you can choose a few—three or four—large branches that will open up the tree but still leave the tree looking balanced.

Patience and Persistence

The author points to a profusion of “water sprouts,” new, upright-growing sprouts caused by cutting back the central leader.

Patience and persistence are the next things you will need to bring these old trees back to a manageable and productive state. Even if you do a good job picking a new central leader or multiple leaders, in the first year and with the first main cut(s), the old tree is almost certain to produce an abundance of upright growing shoots sometimes called “water sprouts.” You will have to be patient and persist in pruning out those upright growing sprouts. Manage this tree to satisfy the criteria leading to good fruit: thin out the interior of the tree for sunlight and air penetration, favor outward-growing limbs and shoots, and always remove diseased wood and branches that are rubbing against each other.

It might take three or even four years before the tree is in a more manageable state and back to producing large, quality fruit. But once and well done, the tree will be back to something much more easily managed and almost certainly more productive.

Find Out More

To learn more about pruning, see the ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture videos Pruning Fruit Trees: Tools and Tips and Pruning Fruit Trees: An Introduction. Feel free to contact the ATTRA help line at 800-346-9140 or email askanag@ncat.org if you have questions. We’re here to help!

Courtesy

Courtesy

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] summer is an ideal time to practice restorative pruning. Pruning activities during the summer include removing dead, damaged, or diseased branches. Many […]

[…] increase their vigor and lifespan, and it is possible to rejuvenate old or neglected trees through restorative pruning. If your wood is overcrowded and poorly positioned, you will be able to develop evenly spaced […]

[…] is an ideal time to perform restorative Pruning. Pruning tasks are typically performed in the summer, such as removing dead, damaged, or diseased […]

[…] the summer, you are best suited for restorative pruning. During the summer, you may have to remove dead, damaged, or diseased branches. It is widely […]

Comments are closed.